The Kuznets Curve

Why Human Prosperity Saves the Planet

By the early 19th century, England had a major problem: they were running out of trees. The problem of deforestation was not a new one, and the English had even become somewhat accustomed to it over the past few centuries. As far back as Queen Elizabeth I’s reign in the 1500s, the English government had been commissioning dozens of investigations into the wood shortage which was already impacting the very foundations of English society. However, despite these investigations the government failed to find any permanent solutions, something that they would soon have to face the consequences of. Because of the useful qualities of wood—strong, waterproof, energy dense, and wide availability—it was used for just about everything and anything, from cooking to ships to paper. In a time before steel, concrete and other modern materials were widely and cheaply available, this meant that wood was being used for a huge portion of material products. Not only this, but wooded areas were also just simply in the way of agricultural development, meaning the trees would get cut down regardless of their practical use. And so, as England continued to gain power and grow, it inevitably consumed more and more wood.

By the 1800’s the inevitable was finally happening. What had been a continuing nuisance for the small but rich island nation for centuries was now rapidly becoming a dire matter of survival. For while this abundant and renewable resource had helped sustain English prosperity for centuries, they were now on the verge of completely running out. If deforestation continued at this rate, soon there would quite literally be no trees left, and English society could collapse.1 Thankfully, the English had lucked out, for as their forests disappeared, they realized that coal (which, ironically, is just ancient plant matter) could substitute for many of the most important uses of wood, such as providing heat. In what would become one of the biggest windfalls of human history, this discovery of coal gave the English a massive boost in the amount of energy they could harness2 which quickly led to what would become the Industrial Revolution.

Why am I telling this story? Because while the Industrial Revolution is today (fairly) blamed for many of the environmental problems that we have had to deal with—air pollution, climate change, acid rain, etc.—very few remember that it was itself inadvertently caused by an environmental catastrophe. For thousands of years humans have been irreversibly changing our environments, and it’s this trait more than anything else that makes us unique in the animal kingdom. While other animals adapt to fit their environments, in what can only be seen as the most successful accomplishment of evolution in its multi-billion-year history, humans have learned to adapt our environments to fit our own needs and desires. Almost definitionally, this trait has always led to massive problems in the environment around us. The only difference between now and then is that there’s a lot more of us, and we are much more consciously aware of the consequences of our actions.

There is this feeling slowly permeating through our society today that we treat the environment far worse than ever before, and that most of it is the fault of the richest nations in the world. But the honest answer is that we have always harmed our environments, regardless of how wealthy we are. Humans have always taken the chance to exploit the world around them, and when we really look at the data, we see that for many criteria it is actually the poorest among us who (per capita) harm the environment the most, such as with deforestation in England when the nation was comparatively poorer to today.

The relationship between human wealth and environmental health is commonly misunderstood as a linear progression. But as with England, it is clear that often the progression of human wealth alleviates environmental problems, even if the new wealth often causes new problems.

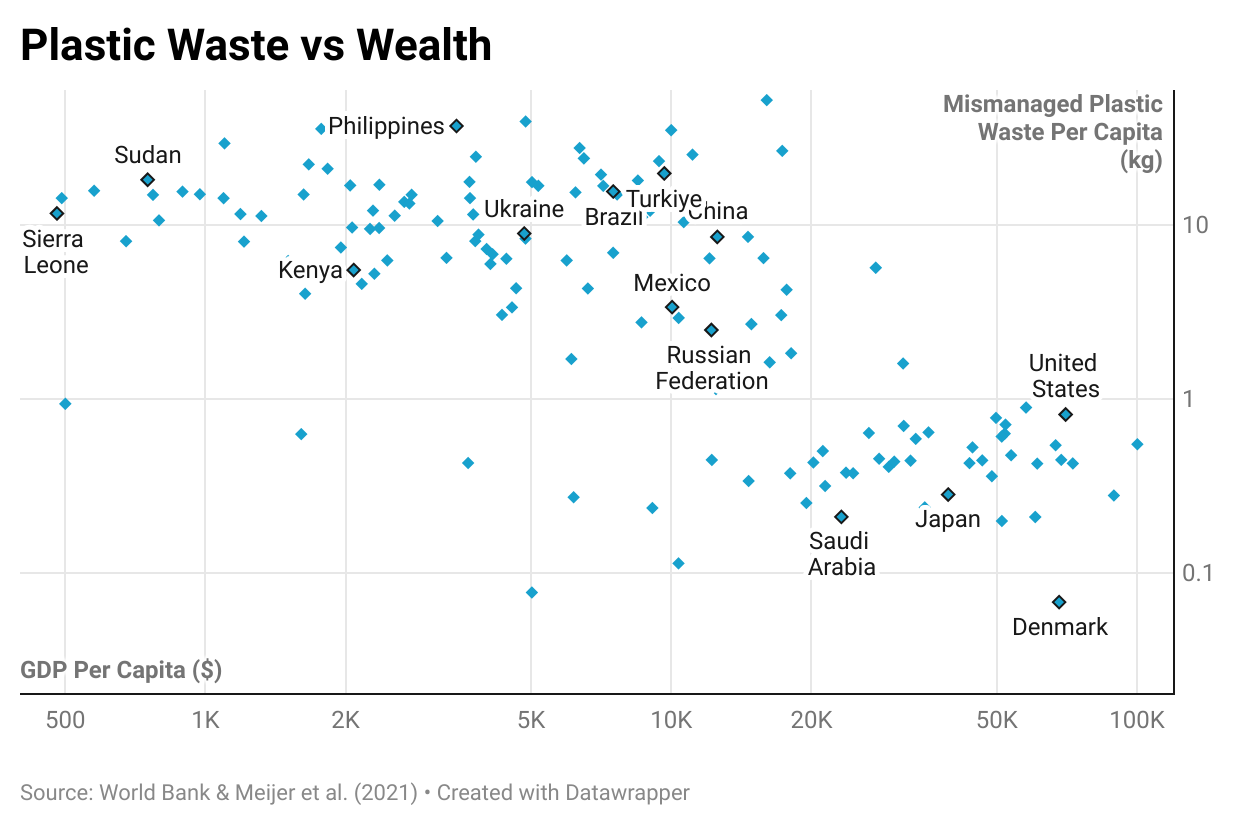

Plastic pollution, for example, is a major non-climate change issue facing the environment. Our civilization produces a staggering amount of plastic, in volumes so huge that the numbers are hard to calculate, though a commonly cited number is around 400 million metric tons per year. While many countries produce huge volumes of plastics, the more interesting metric is which countries dispose of their plastics properly. The best comparison here is between the two plastic powerhouses of the world, the United States and China. Despite the United States producing nearly triple the plastic waste as in China each year on a per-capita basis, China produces ten times as much mismanaged plastic waste as the United States (again, per-capita). However, China is far from the worst offender. Intriguingly, it is almost universally true that the poorer the country is, the higher the rate of plastic mismanagement, which describes the amount of non-contained plastic that inevitably ends up in rivers, oceans, and animals. The average Chinese citizen is about 50% wealthier than your typical Turk, but produces less than half as much mismanaged waste, and Filipinos create twice the waste of the comparatively wealthy Turks. As the chart that I made below shows, as GDP per capita increases, mismanaged plastic waste decreases, with a massive drop off in waste occurring between $10-20,000.3

Similar trends can be seen for a wide variety of other environmental problems. The death rate from air pollution has nearly halved over the past 30 years, deforestation rates peaked in the 1980s, and for many of our current issues we see environmental degradation decreasing not just due to individual countries becoming richer, but because the world as a whole is getting richer and banning harmful substances such as lead and ozone-depleting chemicals on a worldwide scale.

The use of lead in gasoline, paint, and pipes is a topic that deserves an article of its own, but since rich countries began banning leaded products back in the 1970s and 80s the global economy has gradually agreed to remove this toxic substance from many products. As a result, the global burden of disease from lead exposure decreased by 30% in the past 30 years. By the year 2000 most of the developed world had already banned leaded gas, with almost all of the remaining countries that allowed it being in Africa, until between 2004-2006 nearly every nation in Africa simultaneously banned the use of it. The last holdout in the entire world was Algeria, who finally banned leaded gas in 2021, marking the end of the atrocious fuel and completing the full global ban. A similar story is still playing out with the legality of lead paint. While nearly every country in the world now has controls on lead paint, the vast majority of the remaining countries without these controls are in poor sub-Saharan Africa. But if history has anything to teach us, it is that change can happen quickly, and we could soon see a global ban on lead paint.

The story of ozone-depleting chemicals such as Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) is similar to that of lead, but even more dramatic. In the post-World War II era, CFCs became popular worldwide for their use as a refrigerant, as it was both more effective and much safer than prior refrigerants. However, CFCs come with the side-effect that when they are emitted, they destroy the ozone layer of the atmosphere, which protects the surface of Earth from harmful radiation coming from space. However, humans had no idea they had this effect until the 1970s when scientists warned of the possible threat and shortly thereafter discovered a massive hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica, which was steadily spreading across the entire globe. Within a decade nations around the world came together and signed the Montreal Protocol, which is today widely considered the most successful international environmental protection law in history. Five years after the Montreal Protocol was passed in 1989, global emissions of CFCs and other ozone-depleting agents had plummeted from 1.7 million metric tons to 500,000 and today they are essentially non-existent.

All of these examples show us a clear pattern. We get a little rich, and then do something really reckless which hurts our environment. But then, as we continue to get even richer we notice the growing problem, mitigate it, and end up in the same spot as before the problem but with the benefit of being much better off both materially and socially. Importantly, each time we have gone through this cycle the world has moved ever closer to valuing the environment, always taking ever more consideration before making decisions than we have in the past. In this sense it is not just individual problems which are mitigated as we become wealthier but also our civilizational viewpoint on how we should treat the environment around us with respect and stewardship.

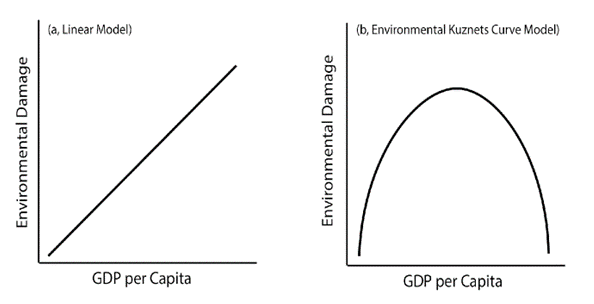

Now we can get to the real point of this article, which I will pose as a hypothetical question: What if instead of environmental damage always increasing as people get richer, it reaches a tipping point somewhere along our development, thereafter actually going down as we continue to develop even further? In other words, what if when we graph our impacts on the world around us, instead of a linear model like graph A shown below, it actually looks parabolic like graph B?

This is called the Kuznets Curve. Put forward by Simon Kuznets, in its original form it measured wealth inequality against GDP per capita, which doesn’t really seem to hold up from what the world has experienced so far, as inequality has risen in some places such as the United States but declined in others like Japan. However, many have begun to adapt the original graph to this “Environmental” Kuznets Curve above, which simply replaces Wealth Inequality with Environmental Damage. Essentially, this curve is proposing that our impact on the natural world increases as we get richer, but eventually reaches a tipping point, where thereafter our impact actually decreases as we continue to get even richer. On its surface, I think many people intuitively understand this trend and recognize that there may at least be some truth to it, with one of the best examples being the modern adoption of clean energy sources and growing regulations involving environmental harm among wealthier nations.

So following the Kuznets Curve model, what are we supposed to do? Well, the answer is right in front of us: if we want to help the environment, the best thing to do is help make everyone—especially the poorest—get richer, ideally as fast as possible. It’s like a get-rich-quick scheme, but instead of having your identity stolen we can save the world.

Of course, many of our current problems not only remain but continue to get worse at terrifying speeds. Greenhouse gas emissions are accelerating us ever farther into a hotter world. Ocean acidification is wreaking havoc on ocean ecosystems. Biodiversity rates are dropping precipitously, leading us towards serious ecosystem collapse. But history and our modern trends give us reasons to be hopeful that these issues and others can also be solved through further development. And of course, clean energy is the key to it all.

As the world gets richer, clean forms of energy will continue to proliferate at accelerating rates, directly reducing our impact on climate change, ocean acidification, air pollution, acid rain, and more. Half of the habitable land in the world is used just for agriculture and livestock, and high clean energy penetration will allow us to dramatically reduce these impacts through lab-grown meats and vertical farming, simultaneously returning huge amounts of the globe back to the natural world while creating a more resilient, efficient, affordable, and healthy food system. With more clean energy we can create more efficient and sustainable modes of transportation such as electric vehicles and new forms of public transit, and we can begin to transition towards a truly circular economy—again mitigating the need for one of our most damaging industries (mining) and opening up more space for the rest of the biosphere.

What the world needs more of—over anything else—is growth. This is why the growing ideology of degrowth is so wrong, and antithetical to their own goals. Those advocating degrowth correctly assess only half the picture, identifying the problem but completely failing to understand the best solution. They see how the growth of our civilization, particularly since the industrial revolution, has caused great pain to our beloved home, but fundamentally fail to understand the bigger picture of why continued growth is the best way to save both humanity and the planet. In an ever-growing world of 8 billion people, human prosperity means natural prosperity.

Numbers on deforestation are hard to come by, but the data that we have for France tell the same story. Historically, forests covered around 50% of France’s land mass, but now that figure had absolutely plummeted, reaching what would become it’s all time low of 13% by the mid-1800s.

The primary reasoning is that coal is simply much more energy dense than wood, meaning that an amount of coal can do much more work than an equal amount of wood.

Take note of the logarithmic scales on the chart. The plastic waste figures comes from a 2021 study, while the GDP per capita figures come from the World Bank.